An Indian’s Take on Beijing

On my way back to India after my first-ever visit to China—a month-long backpacking trip across the country—I found myself upset at the proposition that it would likely be my last. During my layover in the Hong Kong airport, I sat morosely swiping through the hundreds of pictures from Beijing, Guilin, Chengdu, and Yellow Mountain on my phone, wishing I could stay longer, just a little bit longer, and experience the country as a resident instead of as a tourist.

The universe has a way of surprising you when you least expect it. Or maybe it was that I wished so hard to go back that destiny had little choice. Just a few months later, I was back in Beijing as a full-time salaried, apartment-dwelling, grumbling-about-tourists-during-Golden-Week member of the population. I registered Taobao and Ele.me accounts (“Ni de waimai daole!” one of the first Chinese sentences I learned: “Your takeout food has arrived”), much to the chagrin of my bank account. I worshipped at the altar of WeChat, spending at least sixty percent of my day finding and adding new stickers to my collection.

I grumbled about being forced to pay cash in other countries when traveling after becoming so used to scanning a QR code for everything. “I thought this was the 21st century,” I sulked while paying in paper bills from ancient times. I started pining for WeChat and Alipay.

During inevitable dinnertime debates about northern vs southern China, I found myself obliged to vociferously defend the former as though I had lived there my entire life and once nearly hit someone over the head with a chuan’er (barbecue) stick. I was delighted to discover that actual Chinese food in China was absolutely nothing like the neon-orange “Chinese food” I had grown up eating back home, “Chindian” as we called it. In China, food involves so much more than noodles and dumplings (though I would happily subsist on just those two for years). After learning about the Eight Major Cuisines of China, I once embarked on a weeks-long project to cook a dish from each culinary school. It was the most I ever cooked in my entire life.

After a vehement struggle, I finally got acclimated to mealtimes much earlier than I was used to in India. Back home, lunch is eaten around 1 p.m., and it’s perfectly regular to sit down at the dinner table around 9 or 9:30 p.m. Before I got used to the new schedule, I was aided by considerable mid-meal snacking—11:30 a.m. was practically still breakfast time for me! Something I thoroughly failed to embrace was a ferocious cultural disdain for air-conditioning. Oh well. Thankfully, my intrepid little desk fan helps greatly. Now if only I could carry it everywhere with me. To be fair, I’m sure there’s already one such contraption available in the vast virtual aisles of Taobao.

I guzzled mug after mug of scalding hot water throughout the day (in every season), ate my own weight in jiaozi (Chinese dumplings) and learned to leap out of the way of a speeding waimai (takeout food) delivery guy. Developing the skill to avoid speeding bikers is how I’m still alive to type this today. That and hot water, of course.

The author at her favorite spicy hot pot restaurant in Beijing. courtesy of the author

The more I navigated the little details missed by tourists’ eyes that make life in China distinct, the more I began to feel at home. That Chinese and Indian customs, habits, preferences share several parallels certainly helped. Many things about familial expectations and cultural norms that perplexed my Western friends were old hat to me. Even the infamous chabuduo culture has an Indian counterpart: jugaad. Beijing’s (very tentatively) organized chaos reminded me of Mumbai. The way social relationships functioned, even similarities in our palates… such pockets of similarity provided great comfort during my first few months in China thousands of miles from home. Even the rush hour battle on the subway felt familiar. But I learned quickly not to assume I could handle spicy food because I had grown up eating it. Chili peppers in China are a whole different level of fiery and I experienced this first-hand after ordering malatang (a kind of spicy hot pot) extra-spicy. I think that meal may have very possibly taken a grenade to my sinuses for life.

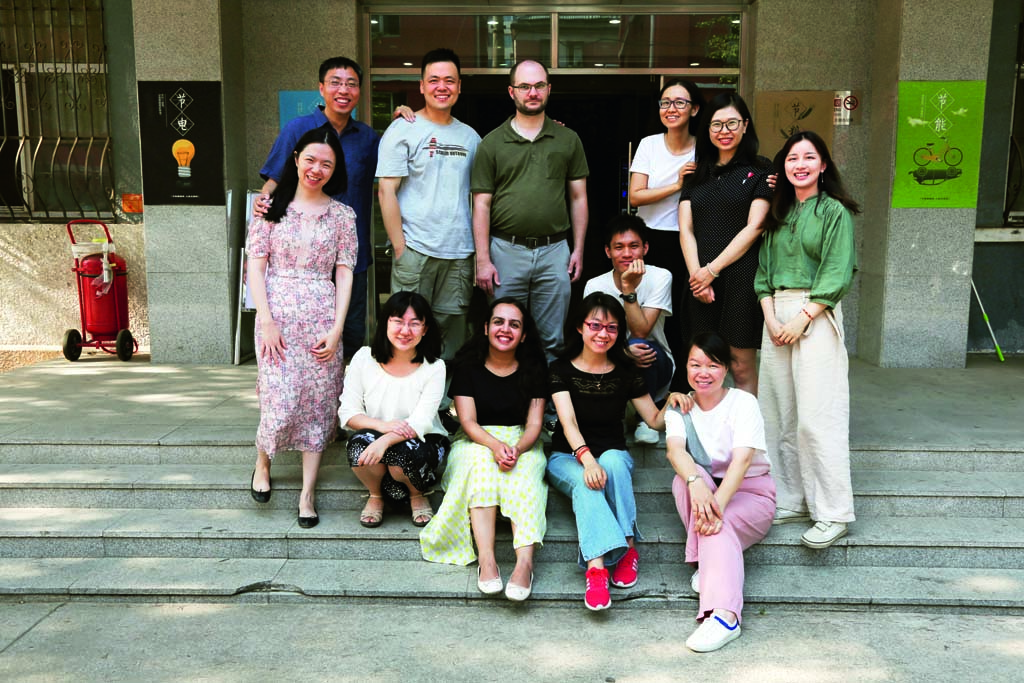

But more than any cultural (or culinary) aspect, the thing that truly made Beijing feel like home was simple: the people. Warm colleagues taught me much, and wonderful friends, both Chinese and other expats, always had my back and accompanied me on some memorable trips. Nina taught me to fold dumplings, Yan introduced me to the unsuspected horrors of baijiu (distilled liquor), and Cici and Dave guided me on a hike along the unrestored Jinshanling section of the Great Wall. Nancy flew with me to Vietnam, and Erica who took care of me when I hurt my ankle and could barely walk.

The brutal summer heat was made bearable by regular doses of extremely milky and sweet milk tea I bought from a small store right outside my office building. My visits became so often that the shopkeeper would have my drink ready by the time I reached the door. For the couple of minutes I was in her shop, I’d practice my meager Chinese with the extremely chatty laoban (literally “boss”), which is what Chinese people call the owner of a shop, and find myself looking up new words in advance so I could expand my chats with her—very, very slowly. Now, if other customers are in the shop, she introduces me as the “pretty Indian girl,” a phrase I must admit I’m thoroughly pleased about.

I’d have similar broken conversations with the old couple who lived next door. Often, when they’d get watermelon, one would knock on our door with a bowl heaping with watermelon slices. Once they delivered an entire watermelon to me and my roommate. It was the size of a (very heavy) football. We loved those visits. In the mornings when leaving for work, I’d sometimes run into the elderly man taking a brisk walk around the community garden or his wife returning from a bike ride. We’d always wave and smile at each other, and when I went out of town, they took care of my plant.

My years in Beijing and China would not have been nearly as memorable, special or fun without the bonds I made. The people I met are what will stay with me long after my time in China ends—hopefully until I can meet them again.