Animator Life Rewind

As the largest and oldest animation production house established since the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, Shanghai Animation Film Studio (SAFS) undoubtedly holds a significant place in the history of Chinese animation. The older-generation animators from the studio were engaged in challenging experiments and exploration to fuel the rise of the “Chinese Animation School” and usher in the golden era of Chinese animation from the 1960s to the 1980s.

Outdoor location shooting has been a long-standing tradition of SAFS due to an unwavering commitment to immersion in real-life experiences before embarking on any film production. For Nezha Conquers the Dragon King (1979), water-related scenes played a prominent role and were characterized by ceaseless motion. To better grasp the nuances differentiating tiny waves, gentle waves, mighty waves, and colossal waves, the team of art designers stood on shorelines to sketch the tumultuous waters approaching the reefs. Seeking to better design underwater characters like the shrimp and crab soldiers and yakshas, the team took field trips to marine aquariums to study oceanic life, engaged with local fishermen on islands, and even jumped into the water of Dianshan Lake.

This is a story recounted in Animators of Shanghai Animation Film Studio: An Oral History (I). The book features interviews with professional animators, researchers and others related to the animation industry who have personally witnessed and experienced the development of Chinese animation throughout the 20th century. Central to the narrative are tales from SAFS retirees, unsung behind-the-scenes heroes who braved the limelight to share the creative journey behind the animation classics.

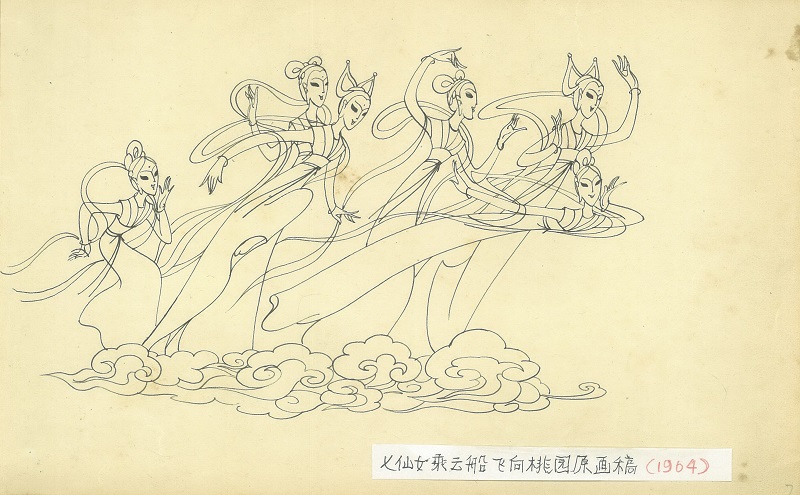

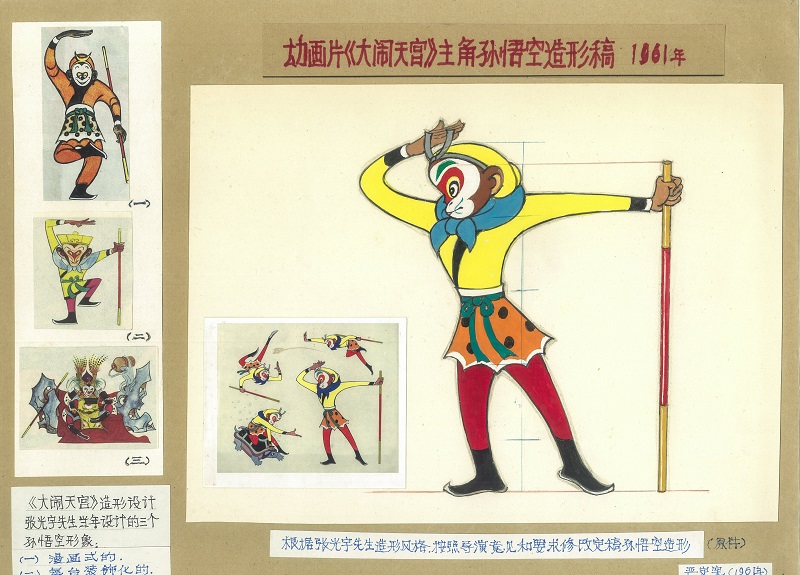

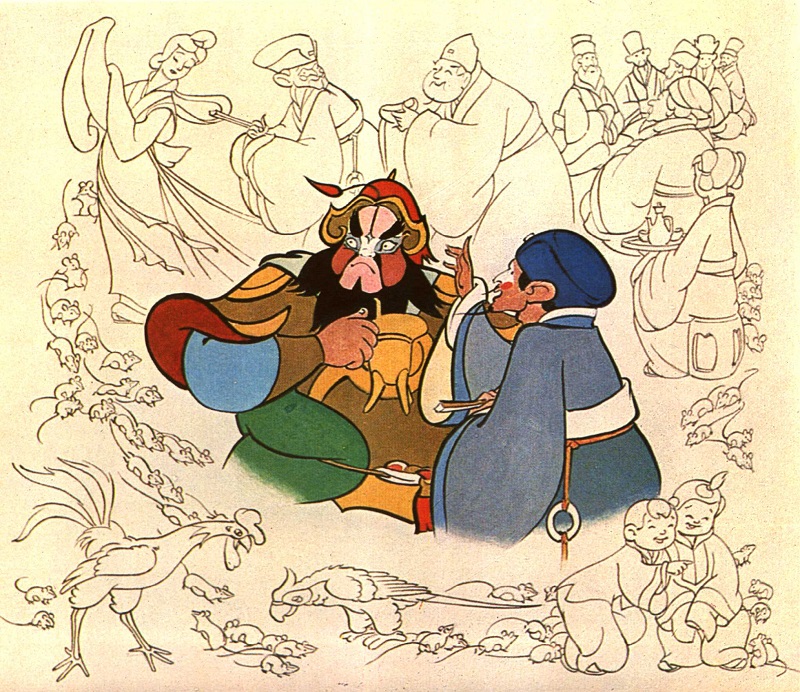

The clouds in Havoc in Heaven (Part One produced in 1961, Part Two produced in 1964) were inspired by relief clouds in Beijing’s Biyun Temple. “Those clouds aren’t flat at all,” reminisced Lin Wenxiao, principal designer for the animated film. “Their stereoscopic quality left us astounded. We found them so captivating that we immediately transfigured them onto the canvas.” And their influence continued. “Previously, we had been drawing those fluffy, cotton-like clouds often seen in American cartoons,” Lin added, reflecting on the profound impact of the relief clouds. “However, Havoc in Heaven marked the turning point when we began to draw inspiration from traditional art.”

As early as the turn of the 1950s, Te Wei, the inaugural manager and director of SAFS, started researching an artistic style with Chinese flavor. “Te Wei had long-standing aspirations to cultivate a distinctive animation style unique to China,” said Lin Wenxiao in an interview.To design character models for The Proud General (1956), the SAFS production team tried to emulate the live-action movements from the Soviet film The Fisherman and the Goldfish. “Our production team enlisted actors from a feature film studio to perform scenes while they meticulously captured their actions frame by frame and subsequently transformed the figures into animated forms. However, upon reviewing the sample footage, Te said that the effect did not align with his vision,” Lin recalled.

Ultimately, the team decided to find inspiration in Peking Opera. The director instructed the production team to watch Peking Opera performances and invited acclaimed actors to deliver lectures to enlighten them on the origins and evolution of Peking Opera as well as methods to appreciate it. The actors also explained how their movements in performances derived from everyday life to be refined and transformed into a choreographed art form. “Once the character designs took shape, there was a collective sense of awe and excitement,” remarked Lin. “We realized that using these designs to create animation would be truly remarkable.”

“This experience compelled all of us that had heard the lectures to prioritize the essence of traditional Chinese culture, and it exerted a direct impact on our future creations,” added Yan Dingxian, a former animation designer at SAFS. “It was a pivotal turning point.” The pursuit of a distinctive Chinese style not only marked a significant milestone in the history of Chinese animation but also laid the foundation for the development of Chinese animated films in the ensuing decades.