Cheng Bushi: My Life on the Wing

During the celebration on the afternoon of May 5, 2017, after the successful maiden flight of the C919, one senior in the crowd was particularly emotional. “China isn’t behind global leaders in aviation by much,” cried Cheng Bushi, a member of the C919 expert team. “We gained experience and built our own team from the Y-10 project, which eventually formed the powerful core we needed to build the C919. In the future, we are bound to face more challenges and overcome more difficulties, but our confidence will only grow.”

One of the first-generation Chinese aircraft designers, Cheng Bushi served as deputy chief designer of the Y-10, China’s first commercial jet airliner developed in the 1970s. In 2007, the C919 project, a plan to develop a domestically-built large passenger jet, was officially approved. In 2008, the Shanghai-based Commercial Aircraft Corporation of China, Ltd. (COMAC), a state-owned aerospace manufacturer devoted to implementing major national projects related to large and medium-sized passenger planes, was established. Cheng was invited to join the C919’s expert team. During the C919’s design and research phase, Cheng oversaw the program from a wider angle and provided consultation on various parts of the plane, including the head, body, wings, and engines, as well as various experiments on things like system integration, static testing and trial flights.

The successful maiden flight of the C919 drew heavy attention to China’s large passenger planes. “I have been involved in China’s aviation industry for more than six decades and designed small as well as supersonic aircraft,” asserts Cheng. “It used to be a sore point that we didn’t have our own jumbo jets. But this makes up for it. I have no regrets now.”

Cheng was born in 1930 in Liling, Hunan Province. After graduating from high school in 1947, Cheng was determined to “build aircraft for the motherland.” “Earlier, I attended a middle school in Guilin, Guangxi, where I saw the Flying Tigers battling the invading Japanese air force with my own eyes,” recalls Cheng. During the Chinese People’s War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression, Guilin served as an air base for the First American Volunteer Group (AVG) of the Chinese Air Force, nicknamed the Flying Tigers. “I wanted to design aircraft like that to take down Japanese warplanes.” In 1947, with great aspirations for the aviation industry, Cheng was admitted by the Beijing-based Tsinghua University. Tsinghua was the first university in China to launch a department of aeronautical engineering, which opened in 1938. With its wealth of brilliant professors including renowned aerodynamicist and aeronautical engineer Shen Yuan and fluid mechanics expert Lu Shijia, the department became independent in the 1950s and eventually became Beijing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics. When Cheng entered the university, China’s aviation industry was quite nascent. While many of his 40-plus classmates eventually decided to change majors, Cheng stuck it out with aviation to the end.

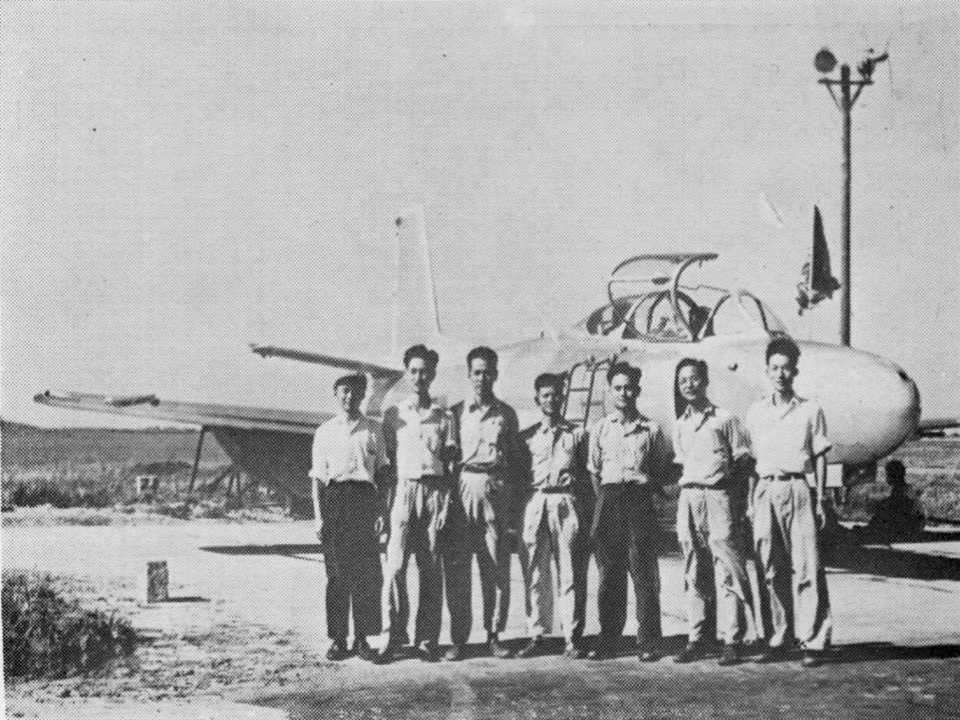

28-year-old Cheng (third from right) stood in front of a Shenyang JJ-1, the first jet independently developed and manufactured by China in 1958.

In 1956, China decided to organize its own aircraft design. Cheng, who was appointed director of the overall design team of the No. 1 Aircraft Design Office, took part in the design of Shenyang JJ-1, the first jet independently developed and manufactured by China, which he considered his first chance to live out his dream.

After World War II, global aviation development gradually shifted focus from military to civilian use. From the flying machine developed by the Wright brothers to modern long-range airliners capable of carrying heavy cargo, the two major breakthroughs in air technology in the 20th Century remain the jet engine and large planes. Cheng has participated in the realization of both breakthroughs in China.

The term “jumbo jet” generally refers to airplanes in transportation categories with a gross takeoff weight of more than 100 tons or trunk liners with more than 150 seats. The ability to produce jumbo jets testifies to the overall development level of a country’s civil aircraft industry and even its overall industrial system. In 1955, the Boeing Company developed the Boeing 707, a long-range, four-engine jet airliner. In 1969, the Airbus A300, the Boeing 707’s European counterpart, was jointly developed, manufactured and marketed by countries including Britain, France, and Germany.

In August 1970, China’s Y-10 project, which aimed to develop a large aircraft, was launched in Shanghai. Cheng joined more than 300 researchers and scientists from more than 40 institutes across China, and devoted all of his efforts to the project. After serving as deputy director of the overall design team for a period of time, he was appointed deputy chief designer of the Y-10. On September 26, 1980, the Y-10 completed its test flight in Shanghai, with a gross takeoff weight of more than 110 tons and a maximum range of more than 8,300 kilometers. An indigenous Chinese design, the Y-10 was China’s first large jet aircraft with all intellectual property rights owned by the country. It was considered comparable to its competitors from the United States, Europe, and the Soviet Union.

However, in 1982, research and development work on the Y-10 came to a halt. In 1986, the project was officially terminated, which Cheng regretted for a long time. The end of the project led to further collapse: Research and development of China’s domestic jumbo jets got disconnected, and brain drain became a major concern. China fell so far behind in jumbo jet technology that it even became a source of embarrassment. “During one international aviation conference, delegates from China were asked to leave the venue early,” glares Cheng. “The foreign host announced that they were going to discuss something we were not supposed to know.”

But Cheng has never given up his dream of developing China’s own large planes. Even after he retired in 1986, he spent considerable time writing in support of the development of Chinese jumbo jets. “We need our own large passenger airliners,” he declared at numerous workshops and seminars across the country. Until the C919 project was formally approved in 2007, he had been writing articles on a blog for science popularization, confronting questions about the Y-10 and emphasizing the importance and necessity of building Chinese jumbo jets.

Cheng spent his entire career making breakthroughs in aviation. Among other things, he achieved supersonic speeds in China’s military aircraft, explored the possibility of large airplanes as well as computer-aided design, and formulated and employed China’s airworthiness standards for civil aircraft. Some have argued that he was not born “at the right time.” If the Y-10 project had continued, not only would China’s jumbo jet development now be at a higher level, but Cheng’s personal achievements would be even more impressive.

Cheng believes that the past three to four decades have represented an inevitably tortuous road during the development of the Chinese nation. The nation continues to march ahead after paying some heavy tolls and correcting its errors. He has remained concerned with helping the country’s aviation industry take off.