Chinese Opera: Traditional Art Revival in the New Era

Like other civilizations in the world, China’s long cultural history included a lengthy history of theatrical performance, but not until the Southern Song Dynasty (1127-1279) did China’s most representative opera, Xiwen, a classical local opera from Wenzhou in Zhejiang Province, emerge. When the People’s Republic of China was founded in 1949, Xiqu became an umbrella term for traditional Chinese operas, with Xi referring to stage performances and Qu scripts mainly composed of rhymed lyrics penned by literati.

Chinese opera literature reached its first peak during the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368). Few intellectuals from the lower class desired to work as an opera scriptwriter during the Southern Song Dynasty, but the profession became more accepted in the Yuan period. Then, many outstanding literary figures tried their hands at this form of art, producing masterpieces like The Injustice to Dou E by Guan Hanqing, The Romance of West Chamber by Wang Shifu, and Autumn in the Han Palace by Ma Zhiyuan, among many others. During the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), opera scripts became longer and more dramatic, and legendary subjects became en vogue in the scriptwriter circles. Classical dramas such as The Peony Pavilion, The Peach Blossom Fan, and The Palace of Eternal Life, now considered the highest achievements of Chinese literature during the Ming and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties, were also very popular when originally staged. At the same time, local operas featuring folk music spread across the country and formed a diverse range of theatrical performances, and Kunqu Opera was the courtliest form favored by high-level intellectuals after the mid-Ming Dynasty.

By the mid-19th century, folk opera troupes from relatively developed areas of southern China had created a new style of opera based on local tunes which became known as Peking Opera. After winning favor from the imperial court and commercial theaters alike, Peking Opera spread across the country and came to dominate theater stages within just 20 to 30 years. After the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, the government adopted the policy of “letting a hundred flowers blossom and a hundred schools of thought contend” to promote progress in arts, so various types of opera from across China were encouraged to flourish and formed the diverse hues of today’s theatrical performance landscape. At least 348 types of opera are performed in China according to the 2017 statistics released by the Chinese government, and national policies have been formulated to maintain and develop their cultural value and artistic characteristics.

In the 1920s, Mei Lanfang (1894-1961), Xun Huisheng(1900-1968), Cheng Yanqiu (1904-1958), and Shang Xiaoyun were four great Peking Opera artists who played female roles in their plays. Before them, only elderly male roles could be the protagonist in a play, but they opened new ground for female roles to serve as the protagonist.The picture shows a still of The Rainbow Pass, starring Mei Lanfang, Shang Xiaoyun and Cheng Yanqiu, with Mei Lanfang (right) playing the young male role. CFB

After centuries of development, Chinese opera has developed as a genre of theatrical performance with unique national characteristics and accumulated tens of thousands of traditional plays. The repertoire covers a wide range of subjects including historical romance and ordinary daily joys and sorrows. The moral principles of “benevolence, righteousness, propriety, wisdom, and honesty” promoted in the plays represent the core values generally recognized by all social classes in China for thousands of years, shaping the way Chinese people behave and live.

However, the ecosystem of Chinese opera has been affected in modern times by the introduction of Western theatrical theory during the New Culture Movement period (1915-1923), the large-scale reform of the traditional opera repertoire in the 1950s, and the impact of modern pop art since the end of the 1970s. Especially in the late 1980s and early 1990s, Chinese opera faced a severe crisis, evidenced by dwindling available plays, dropping performance caliber, and a shrinking market.

In the 21st century, the trajectory of Chinese opera rebounded. Chinese opera experienced a renaissance of sorts as the opera community began better recognizing the significance of inheriting traditional operas and maintaining national characteristics. At the same time, more young people keen on embracing traditional Chinese culture have been drawn to traditional opera. In recent years, old and new plays from different types of opera, including Peking Opera, Kunqu Opera, Shaanxi Opera, Shanxi Opera, and Yunnan Opera, have been well received.

In 1960, a teacher at the National Academy of Chinese Theatre Arts showing students how to play a musical instrument. by Zhang Xiushen and Wang De/China Pictorial

The public’s growing awareness of the benefits of protecting cultural diversity and Peking and Kunqu operas’ addition to the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage List have inspired greater efforts to explore, adapt, and stage the traditional repertoire. Many local opera forms now under protection are rekindling their vibrancy. Distinctive local dialects, music, and traditional performance styles are helping many once-obscure plays attract niche urban audiences.

Moreover, Chinese opera has gone global, showing the world excellent contemporary Chinese works and performances while boosting public confidence in the contemporary development of Chinese opera. Even French scholar Voltaire translated The Orphan of Zhao, a play from the Yuan era, during the 18th century, and Cantonese Opera was introduced to the Americas in the 19th century. When Peking Opera artist Mei Lanfang led his troupe on a visit to the United States in 1930 and the Soviet Union in 1935, the beauty of Chinese opera finally became widely recognized by mainstream Western society.

After the 1950s, Chinese opera got more chances to be performed on the international stage, which helped reaffirm its aesthetic status and artistic value through a positive process of cross-cultural communication. The rapid development of the internet and new media has also created new opportunities for Chinese opera to flourish. In 2020, the COVID-19 outbreak pushed theatrical performance to online platforms. Opera troupes started livestreaming performances and attracting fans on short video platforms like TikTok and Kuaishou. The latest social trends have effectively cut the distance between traditional opera and young viewers.

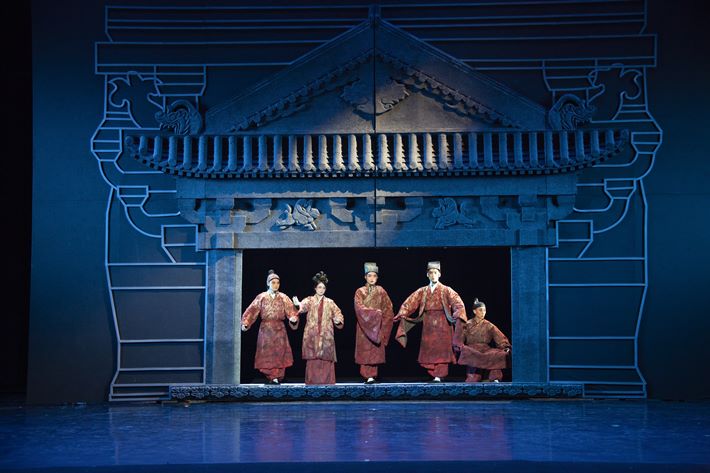

June 26, 2016: A performance is staged at the National Academy of Chinese Theatre Arts, presenting the beauty of visual art on the opera stage. by Wu Xianquan

Despite long-term efforts, the ecosystem of Chinese opera hasn’t been completely restored yet. China still has a long way to go in translating supportive policies for traditional art into measurable theatrical progress, staging more excellent traditional plays, producing new plays reflecting modern times and the contemporary unique features of local places, improving performance, attracting bigger audiences, and protecting hundreds of endangered opera forms. Luckily, the Chinese opera community is working hard on all of these fronts. Thanks to its historical profundity and attractive cultural flair, Chinese opera is likely to relive its past glory in the near future.

The author is vice chairman of the China Literature and Art Critics Association.