David Ferguson, a Foreign Lens into China

“People can thumb through them to get an idea of what I have been working on,” grinned David Ferguson about the armful of books he toted.

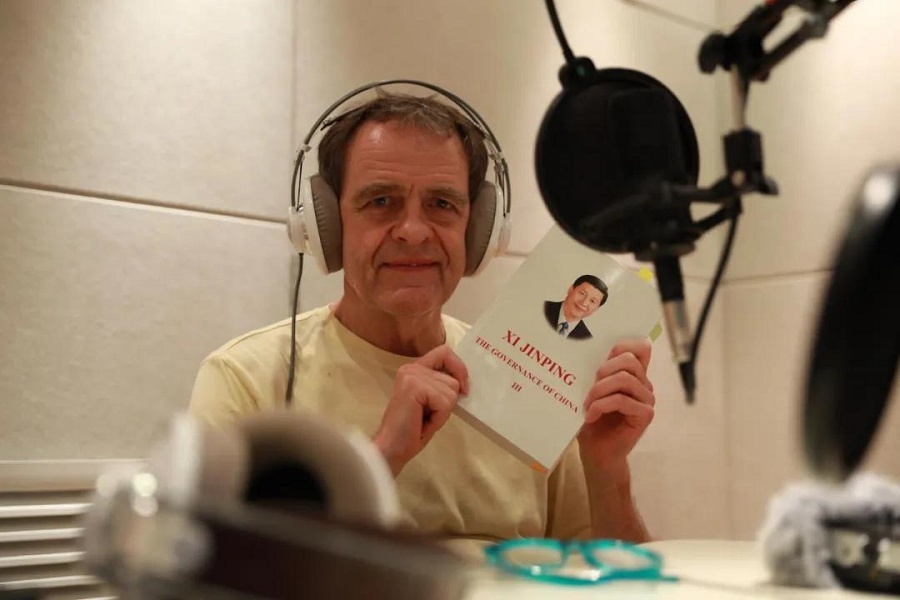

In part thanks to these works, the British expert from Foreign Languages Press of China International Publishing Group (CIPG) became a laureate of both the 15th Special Book Award of China and the latest Chinese Government’s Friendship Award. Ferguson’s prestige was not won in a day, and professionally he is well-known as the main English editor of Xi Jinping: The Governance of China, volumes one through three.

“How many times have you read Xi Jinping: The Governance of China?” Ferguson asked reporters when they interviewed him. “Have you read them more than once? I’ve read Books Two and Three at least five times,” he said proudly.

David Ferguson received the Friendship Award from the Chinese government on September 30. courtesy of Foreign Languages Press

But his relationship with China didn’t start there. Once a law major at University of Edinburgh, Ferguson never practiced law but instead became a management consultant before co-founding a Manchester-based video and television production company with his brother that “didn’t quite manage to break through the glass ceiling.” Looking for a new challenge, Ferguson embarked for China in 2006 with his Chinese wife and first became a football agent before joining the Chinese media in 2008.

“I guess giving that up was the biggest financial mistake of my life,” said Ferguson of the football endeavor. “If I had carried on as a football agent in China, I would be rich by now. But I don’t have any regrets. Otherwise, I would be on a different career path.”

In March 2008, a month before Ferguson was hired by China.org.cn., violent riots in Tibet brought “two completely different stories.” He determined that the western account of the news was “a pack of lies,” which motivated him to take the job. “Rather than trying to paint a picture of what China was saying, I was very carefully researching what the western media were saying and challenging their versions.” His style is well-exemplified by his coverage of the Wenchuan Earthquake and the Beijing Olympic Games, among many other important events.

“I decided at least some person should try to do whatever they could to tell a more truthful and honest story,” he said. “For example, I wrote about stories leading up to the Beijing Olympic Games. There were some negative stories about how 1.5 million Beijing residents had been evicted from their homes to make way for the Olympics.”

Speaking of telling China’s stories, Ferguson quoted Chairman Mao in 1942 on writing for the Communist Party of China: “As a form, the Party stereotype is not only unsuitable for expressing the revolutionary spirit but is apt to stifle it.” He cited the 2019 movie My People, My Country, which commemorated the 70th anniversary of the founding of People’s Republic of China (PRC) as an exemplary case of telling the stories of critical events. “Instead of telling the story of a certain event, it used the event as a backdrop to tell a human story about some persons or people who were related to the event in some way or other,” he said. “China needs to make much more use of its soft power.”

Since 2010, Ferguson has worked as a writer and editor for Foreign Languages Press where he joined the Xi Jinping: The Governance of China project. Alongside tight deadlines, managing with material “not originally scripted or prepared for a western audience” became Ferguson’s focus. The proofreading process has also helped Ferguson develop a deep understanding of President Xi Jinping’s philosophy. “It’s a huge structure with more detail at each level—starting right at the top with the Chinese dream, working down through a series of layers from the Two Centenary Goals and right down to the level where people actually start doing things,” he said.

For non-Chinese curious about Xi Jinping: The Governance of China as a window to China, Ferguson suggested they focus on “concrete stuff about people doing things like poverty alleviation and anti-corruption campaigns…” and “be prepared to invest time and effort in (reading) it.”

“Xi Jinping is the president of China, not a stand-up comedian,” he said. “His job is not to entertain people but to talk about difficult things.”

Ferguson’s work with China has extended far beyond the political realm. Foreign Languages Press invited him to write stories about city landscapes and culture in China, among which are Nantong Tales: Pioneers from “China’s First Modern City” (2011), In Red-embroidered Shoes: Sipping the Essence of Suzhou (2012), and Building a Green Beijing (2016). In the future, he plans to write on poverty alleviation and building a beautiful countryside in northwestern China’s Gansu Province.

Building a Green Beijing (2016) is about Beijing’s wide-ranging eco-environmental initiatives supported by various interest groups. courtesy of Foreign Languages Press

Also, Ferguson is an occasional translator of Chinese poetry relevant to his writing – “listening to the patterns of the poems in Chinese and getting the sense of melodrama.” He was confident enough in his translation to share his favorite, Night Mooring by Maple Bridge by Zhang Ji of the Tang Dynasty (618-907). “I thought I could make it rhyme without turning it into doggerel...”

Night Mooring by Maple Bridge

Zhang Ji (c. 715-c. 779)

The Moon falls, a raven calls, frost fills the sky,

Maple boughs, a fisherman’s lamp, sleepless in sorrow I lie.

Outside the Gusu City wall, from Hanshan Temple knells,

Forth to my barge’s mooring post, the toll of the midnight bell.