Empathy for Animators

Many have experienced yawning being contagious. Others can’t help but do it after seeing someone else yawn. It was until 1996 that the scientific rules behind the phenomenon were discovered by Italian scientists Giacomo Rizzolatti and Vittorio Gallese.

They used the brain scanning technology to discover that when one monkey made a certain action, the corresponding area in the brain of another monkey that saw the action activated. The mechanism to influence the actions, expressions, and emotions of others is unique to higher primates, including humans, which is called the mirror neuron.

The discovery of the mirror neuron proved that empathy, a psychological feature unique to humans, has a true physiological basis. Not only are we affected by other people’s yawns, but we can also feel happy just by seeing happy people on the streets of festivals. Humans are the only creatures that hold funerals for others and become sad for other people’s sorrow and pain. We can be moved by stories and deeply affected by the happiness and sadness of characters in a book or movie.

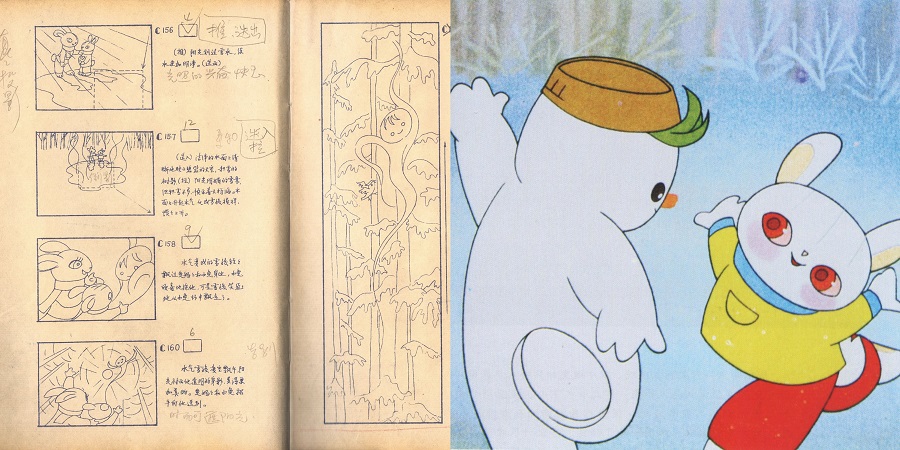

Some layouts and sketches of the animated film Snow Kid (1980) and a still from the film (right), which is a tear-jerker story about love and courage. (Photos courtesy of Kongzang Animation & Comics Archive)

But it is empathy that enables people to love and help each other, empowering our evolution into a highly-socialized species of extraordinary civilization.

Humans are primates who excel at empathy. We can travel across time and space to be touched by ancient Chinese stories such as The Foolish Old Man Who Moved Mountains and Jingwei Filling up the Sea. We can understand cultures from other countries and times and learn and improve emotional skills for social life from characters in stories.

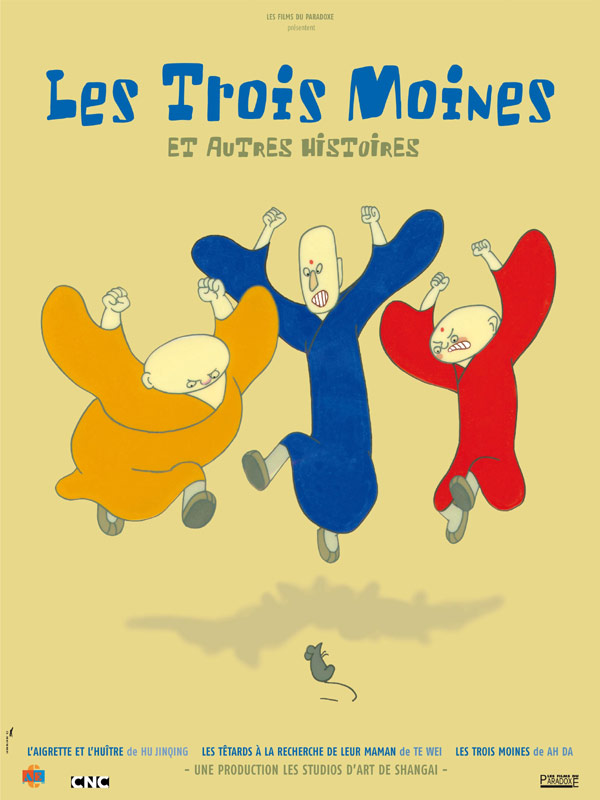

The French poster for the animated short film Three Monks (1981), which reflects a Chinese folk proverb emphasizing the importance of unity. (Photo from Douban)

The same is true for animation. While watching Spirited Away, directed by Hayao Miyazaki, we follow Chihiro’s perspective into a fantasy world to be moved by the little girl’s experience and growth. We shed tears to the song “Remember Me” in the final scene of Coco and sigh for the passing of the times and the uncertainty in life.

The key factor for animation to bridge different cultures isn’t cool pictures or complicated technology but touching stories capable of evoking empathy from a global audience.

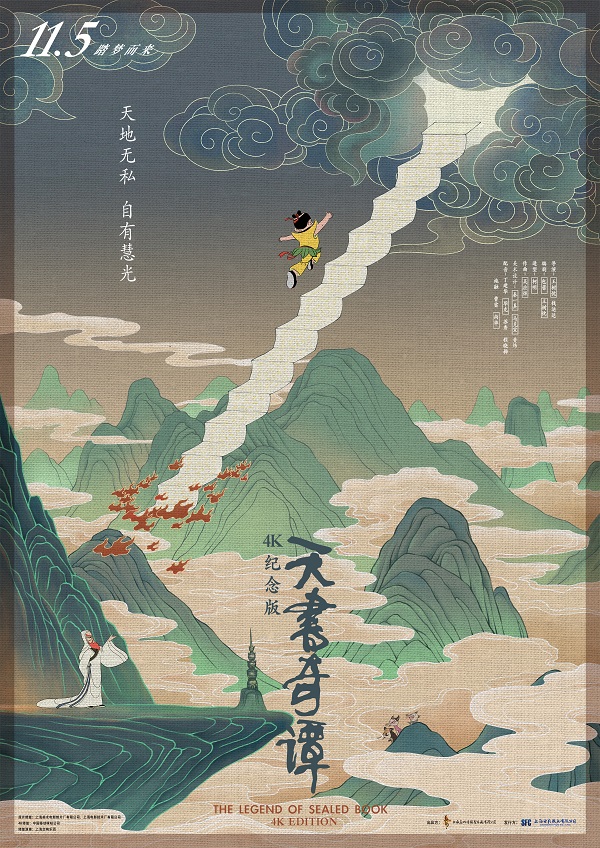

The Legend of Sealed Book, produced by Shanghai Animation Film Studio in 1983, was adapted from The Three Sui Quash the Demons’ Revolt, a novel from the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), which is full of grotesque fantasy and profound enlightenment. (Photo from Douban)

Norman Hollyn, a late professor of film studies at the University of Southern California, vividly described an audience’s movie- viewing experience as two sitting postures. One is “leaning forward,” when the viewer is deeply moved by the fate of the characters and immersed in the story. The other is “leaning back,” when the audience keeps a distance from the story and the characters and judges the happenings calmly.

In the animation industry, creators, of course, hope to create more “leaning forward” moments so the audience can empathize with the characters. However, they often get trapped in an overemphasis on technology and obsess about the form of the movie.

As storytellers, animators should take story logic even more seriously and spend more time depicting the desires and dilemmas of the characters. Even for stories set in a fantasy world, the characters should still be flavored by real personalities and psychology.

A still from the animated film White Snake, which reinterprets a Chinese folktale from a modern perspective. (Photo from Douban)

A character in Russian writer Fyodor Dostoevsky’s novel The Brothers Karamazov says, “The more I love humanity in general, the less I love man in particular, and vice versa.” Love for another culture, era, or country always emanates from empathy for a specific person or role, rather than from impressions of some abstract concepts or symbols. Film production technology, art, and story topics are important, but they are all secondary to characters that evoke empathy.

The author is a professor and dean of the School of Animation and Digital Arts at the Communication University of China.