Hardly Child’s Play

95 Years Old

Chinese movies for children appeared alongside the emergence of modern children’s literature in the country. During the New Culture Movement between 1915 and 1923, Chinese children gradually began receiving greater public attention thanks to ideological enlightenment and the introduction of Western educational methods. During this time, subject matter intended for children attracted movie producers in China.

The first Chinese children’s movie in history, Naughty Child, was a short one released in 1922 and starring children. It was followed by the first full-length feature film, An Orphan Rescues His Grandpa, in 1923. Soon thereafter, in the 1930s, many Chinese kids’ movies featuring cultural appeal highlighted by concern for social reality and moral education were released, including My Dear Brother and Wanderings of Sanmao.

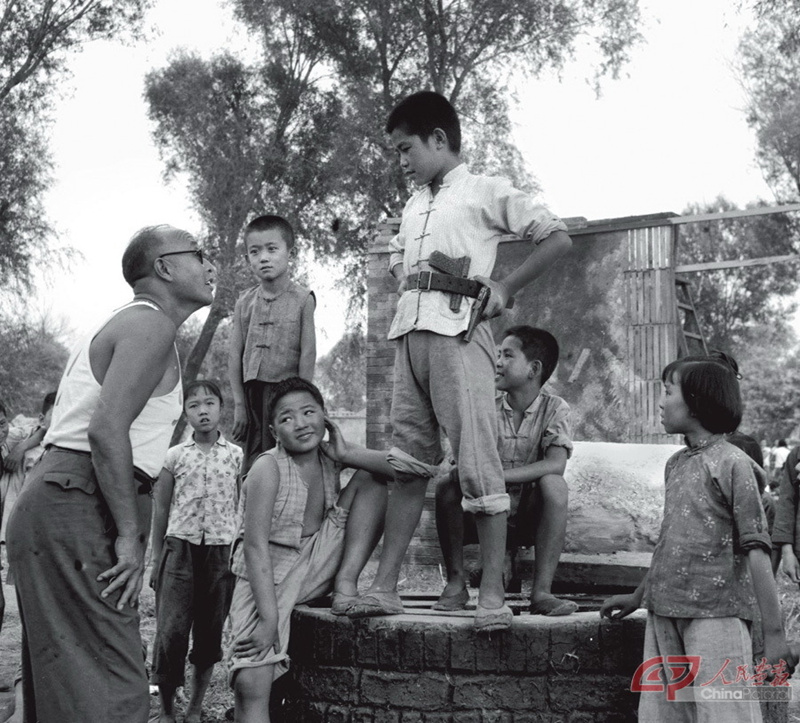

After the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, many “little heroes” of the revolutionary era were sculpted, such as brave and resourceful Hai Wa from The Letter with Feathers, kind and smart Zhang Ga in Zhang Ga the Soldier Boy, and clear-thinker Pan Dongzi in Sparkling Red Star. Written as miniature versions of grown-up heroes, the maturation of such characters mirrored Chinese revolutionary history and inspired millions to attempt heroic deeds.

China’s implementation of reform and opening-up policies in the late 1970s brought dramatic changes to movie production thanks to a more favorable cultural environment and rapid economic progress. In the years that followed, a more diverse stream of films covering a wide variety of topics and forms emerged, including hyper-realistic plots, science fiction films, war epics, ethnic minority movies, and animation. In 1999, The Straw Hut, a film adapted from a novel of the same name by Professor Cao Wenxuan of Peking University that would eventually go on to win the Hans Christian Andersen Award in 2016, hit big screens. The movie followed the childhood of the innocent Sang Sang with a plain tone and simple film language and heralded a pleasant shift to nostalgic flavor and poetic flair, as well as transforming the traditional heroic tendencies of protagonists.

Today, Chinese children’s movies have gone global and won acclaim from spectators around the world, including many that have been honored at international film festivals such as Oh! Sweet Snow, Drummers from the Flaming Mountain, and An Answer from Heaven, which consecutively took prizes at the Berlin International Film Festival for three years in a row.

Feature-length Animated Films

The first Chinese animated film was The Princess of Iron Fan in 1941, which attempted to create a unique style featuring traditional Chinese culture. It was followed by productions so inspired by traditional Chinese painting and folk art that the “Chinese School” of animation, characterized by water and ink, paper-cuts and shadow puppets, emerged. Standouts of the era include Uproar in Heaven, Nezha Conquers the Dragon King and The Three Monks, all produced by Shanghai Animation Film Studio. They were honored with many domestic and international awards including the China Golden Rooster Award, the Gold Award at the Denmark Odense Fairy Tale Film Festival, the Silver Bear Award at the Berlin International Film Festival, and the Best Picture at the London International Film Festival.

Since the turn of the 21st Century, the volume and diversity of Chinese children’s movies have both expanded, and they have heavily impacted the market thanks to the acceleration of the systematic reform of movie production and upgrading of the Chinese movie industry.

From 2006 to 2010, China produced an average of 50 children’s movies annually. Statistics show that in 2016, over 60 animated movies hit screens in the country and earned a total of 6.8 billion yuan at the box office, an increase of 50 percent over 2015. Kung Fu Panda 3, a Chinese-American joint production, grossed more than a billion yuan, and Big Fish & Begonia, a completely domestic Chinese animated movie made on a budget of 30 million yuan, earned 560 million yuan at the box office. Still, most Chinese animation in general struggled in theaters, and many couldn’t recover their costs.

“High-concept animation” dominates the American industry. Producers at Disney and DreamWorks collect ideas from around the globe, fuse American elements with other cultures such as the Arab world in Aladdin, Polynesia in Moana and China in Kung Fu Panda, and add chart-topping songs, a formula that usually results in box office domination and the birth of merchandising goldmines.

American animators have developed sub-genres such as fantasy, adventure and Western, built complete industrial chains supported by world-class marketing, and pursued revenues via diverse channels. Americans have popularized their animation works around the world via an endless stream of creative ideas and a mature industrial mechanism.

China’s animation producers still struggle to compete with their American counterparts in terms of creativity, while enduring the pains of a less mature industrial chain. Productions with tiny budgets and understaffed teams result in mediocre output, a cycle that will be hard to overcome without a real upgrade in the industrial chain.

However, the upgrade of internet+ industries has brought opportunities for the development of children’s entertainment in China. In October 2015, Alibaba Pictures launched the Plan A program in an attempt to establish an animated IP incubator system, with an investment of 1 billion yuan for excellent talent working in animation, design and special effects. At almost the same time, Enlight Pictures established an animation group, Coloroom Pictures, with the aim of capturing a big share of Chinese animation production. The influx of capital and talent has kick-started progress in China’s domestic children’s film industry.

“We can hardly compete with our American rivals with what we have,” admits Sun Lijun, dean of the Animation School of Beijing Film Academy. “We can’t guarantee stable investment, regardless of how good an idea is. It’s extremely difficult to make an animated movie in China due to technical and artistic problems and the fact that many investors want to see immediate profits.”

Excellent products require a long-term vision of the big picture from ideas, topics and characters to structure and values. The only way Chinese producers can stand out among their counterparts around the world is to innovate with inspiration from their own traditional culture and build a more solid industrial chain for animation.

The author is a Ph.D. candidate at Beijing Normal University.