Juraj Krasnohorsky: Reviving CEE Animation

Like many others who grew up in the Central and Eastern European (CEE) region, Juraj Krasnohorsky was immersed in the captivating world of small animated series and short films from countries such as Poland, Hungary, and Croatia. These nations, connected by a shared love for storytelling, co-produced and shared their content, fostering a common tradition of bedtime stories accompanied by seven-minute animated shorts.

In the vibrant world of animation, the CEE region has long been known for its rich tradition of producing captivating animated films for children. Today, ambitious new projects are on the horizon as part of a growing wave of animated films targeting children and their parents across Europe. In an exclusive interview with China Pictorial, Juraj Krasnohorsky, a producer based in Bratislava, Slovakia, and head of studies for the CEE Animation Workshop, shared his experiences, insights, and aspirations for the region’s burgeoning animation landscape.

Building a Collective Vision

Before embarking on his filmmaking career, Krasnohorsky pursued studies in physics and mathematics and even worked as a physicist in Geneva. However, his insatiable curiosity constantly drove him to seek new opportunities and venture into uncharted territories. By living in various countries including Switzerland, France, and Spain, Krasnohorsky gained a rich cultural experience that continues to empower his work as a producer. With a deep appreciation for the diverse audiences across different countries, he endeavors to create films that resonate with wide European viewership.

Reflecting on the animation industry in Slovakia, Krasnohorsky acknowledges the challenging period in the 1990s when the state-controlled animation studios underwent privatization, leading to a significant halt in production. However, in recent years, small studios have gradually reemerged, and the industry has witnessed a resurgence. Despite many persisting challenges, the CEE region has always produced an abundance of talent. Recognizing the need for collaboration and resource sharing, industry professionals established the CEE Animation Workshop in 2017 as a transnational association to consolidate producers and animated film associations from countries across the region and propel growth by providing professional training and project development opportunities. Through the initiative, producers and their teams are gaining the necessary skills to access European financing like their Western European peers and foster collaboration among diverse countries within the region. The workshop has become a catalyst for CEE animators to co-produce ambitious projects and create a collective vision while addressing the costly nature of animation and the need to join forces.

One success story was the film White Plastic Sky, a post-apocalyptic animated feature co-produced by Hungary’s Salto Films and Krasnohorsky’s company, Artichoke. This visually stunning and philosophically profound film earned a place in the competitive Encounters section of the Berlinale. It tackled pressing environmental issues and timeless ethical questions by leveraging aesthetic and technological strengths. The collaboration involved 2D animation production in Hungary and 3D animation accomplished in Slovakia. By assembling these elements, the filmmakers were able to bring the story to life, emphasizing the importance of talented creators and their narratives. While Slovakia has been active in producing short films, the opportunity to venture into feature films finally emerged.

A still from the animated feature White Plastic Sky, co-produced by Hungary and Slovakia. (Photo courtesy of Juraj Krasnohorsky)

Krasnohorsky can attest to the profound impact of the CEE Animation Workshop. The quality of projects has significantly improved, leading to increased participation in prestigious European platforms and competitions such as the renowned Annecy International Animated Film Festival. This growth signifies a transformative shift in the region’s animation industry, with emerging talent from institutions like MOME in Budapest, Hungary, showcasing unique directorial and artistic voices.

The CEE animation industry is now poised at the threshold of a new era, driven by heightened ambitions and a desire to create ambitious series and feature films. This wave has rolled beyond the region, with animation for adults gaining traction throughout Europe. While reaching adult viewers presents challenges compared to children’s animation, the allure and potential for success remain strong.

Opportunities and Challenges

The CEE Animation Workshop is a hub for cooperation. It attracts participants from across Europe and beyond while actively encouraging collaboration with producers worldwide. Krasnohorsky, a firm believer in the power of co-production and co-development, recognizes its potential to unite countries with varying production capacities. To pave the way for fruitful co-production opportunities, he emphasizes the creation of robust networks through events and organizations such as the Annecy International Animated Film Festival and the Annecy International Animated Film Market.

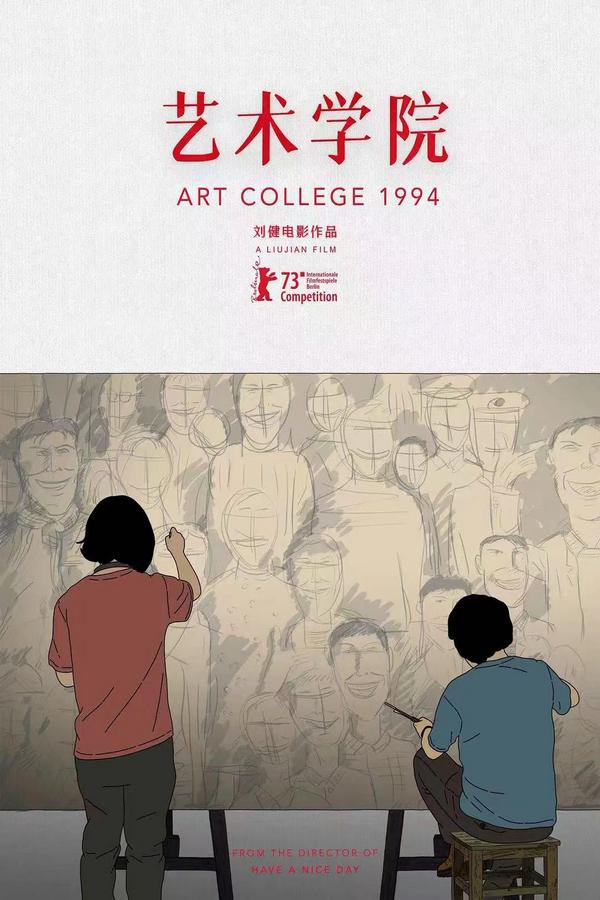

Acknowledging the untapped potential of the Chinese animation industry, Krasnohorsky admitted limited knowledge but remains aware of the aspirations among China producers to share their distinctive local narratives with a global audience. Specific Chinese films caught his attention, such as Liu Zhong’s Art College 1994, which competed at the prestigious Berlinale. The CEE Animation Workshop is now working on cross-cultural cooperation through a joint endeavor with filmmakers in Hong Kong on the animated documentary Ah Cheung. The 2023 project explores how Ah Cheung transcends physical limitations and fosters inclusion within the community through an unwavering spirit.

A poster for Liu Zhong’s Art College 1994. The animation is a portrait of youth set on the campus of the Chinese Southern Academy of Arts in the early 1990s. (Photo courtesy of Douban)

To strengthen ties and promote collaboration, Krasnohorsky has encouraged Chinese producers to actively engage in workshops and market events like Bridging the Dragon and Ties That Bind. These platforms provide invaluable opportunities to understand diverse artistic tastes, exchange ideas, and forge meaningful partnerships. Beyond China, Krasnohorsky is involved in initiatives such as the ATF-TTB Animation Lab, which aims to bridge Asian and European producers and nurture future co-productions. His optimistic vision features a thriving creative content landscape driven by a growing appetite for diverse local stories and an array of financing options.

Krasnohorsky acknowledges the growing presence of artificial intelligence (AI) within the animation industry. He champions integration of AI as a creative tool and holds that it parallels to past technological advancements that revolutionized the field such as the introduction of 3D in the 1980s. Krasnohorsky believes that AI can empower creators to explore daring and imaginative storytelling as well as pave alternative financing paths. However, he emphasizes that AI can never replace the essential role of human creativity. The director, at the core of every film, meticulously selects what is included or excluded to ensure the artistic vision remains intact. AI could serve as a valuable supportive tool while never threatening the creative process.

Addressing challenges faced by independent animators, Krasnohorsky highlights the recent hope fostered by the rise of video-on-demand (VOD) platforms in the form of significant investments from platforms like Netflix. However, over time, enthusiasm has waned, resulting in decreased or stalled investments. Independent animators have expressed frustration with the presentation and visibility of their works on such platforms when they get lost deep below algorithmic recommendations. In light of these challenges, Krasnohorsky asserts that traditional cinemas remain the optimal platforms for independent animation to reach an audience. He emphasized the stark contrast in film reception, with many independent films reaching a mere 10,000 viewers on VOD platforms after 200,000 viewers saw the work in cinemas. While VOD platforms may still wield potential as secondary distribution channels, Krasnohorsky emphasized the captivating and engaging power that cinema houses offer to truly showcase and appreciate independent animation.