Living Alongside Nature

In a fast-paced modern society, rural life has become a yearning for many. Urbanites are often fascinated by scenes of bountiful crop harvests, lush branches, green-blanketed fields, curls of cooking smoke, and busy figures, but rarely experience it up close.

The authors of Satoyama Life of Intellectual Farmers, Chang Jiaoling (real name Zhao Tianxiao) and Wen Zizi (real name Zhang Hehe) born in the 1980s, abandoned the convenience and hustle of urban life in favor of becoming self-sufficient farmers in Beijing’s suburbs, setting an example for people with farming dreams.

They met at the Norwegian University of Life Sciences and bonded over a common interest in nature. After graduation, they returned to China and joined a well-known non-governmental organization (NGO) focused on environment protection. This afforded them frequent opportunities to venture into the wilderness to visit endangered species, where they became acutely aware of the terrible consequences of human ignorance and destruction of the eco-environment and wildlife.

Worried that modern city life had driven people too far from nature, they sought to discover wild secrets in undeveloped corners where people neglected to explore sustainability and co-existence in order to prove that modern people could still find opportunities to live in harmony with nature and appreciate other forms of life. One day, the pair, who had been hunting for nature everywhere, decided to move away to the mountains.

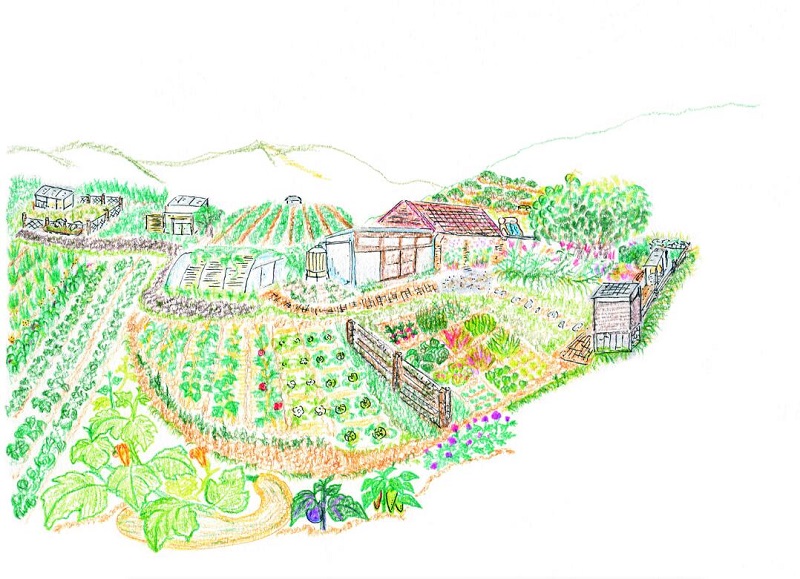

In 2014, they established the Gaia·Ås Garden in the northeast corner of suburban Beijing on a two-hectare land plot that includes crop fields, orchards, vegetable gardens, and houses. Ever since, they have been living a “satoyama” life, working regularly from sunrise to sunset.

Satoyama is not a place name but a Japanese term referring to the border zone or ecosystem between foothills and arable flat land, integrating residential communities, forests, and farms.

Literally, “sato” means “village,” and “yama” means “hill or mountain.” Satoyama emphasizes maintaining the integrity, harmony, and biodiversity of ecosystems.

In a satoyama landscape, forests, streams, grasslands, farmlands, orchards, and houses are integrated with each other. People can obtain the natural resources they need directly, while the environment stays vibrant and lush.

In the book, the authors describe their satoyama garden this way: “A smaller half is made up of farmlands, orchards, houses, and an animal husbandry zone with more than 200 chickens, 30 sheep, five geese, three rabbits, two cats, and five dogs. The other half is an uncultivated forest. It takes five minutes to get to our neighbor’s house and 50 minutes to get to a grocery store in the village, where the nearest bus station to town is also found.”

Chang and Wen chose to live a satoyama life, but they didn’t follow the usual lifestyle of local farmers nor of transient visitors to the sticks who usually arrive on Saturday morning and return to the city on Sunday night, satisfied with a weekend of farmers’ barbecue. This pair took on the role of “intellectual farmers” toiling in the fields and “professional nature observers” who record rural life with images and stories.

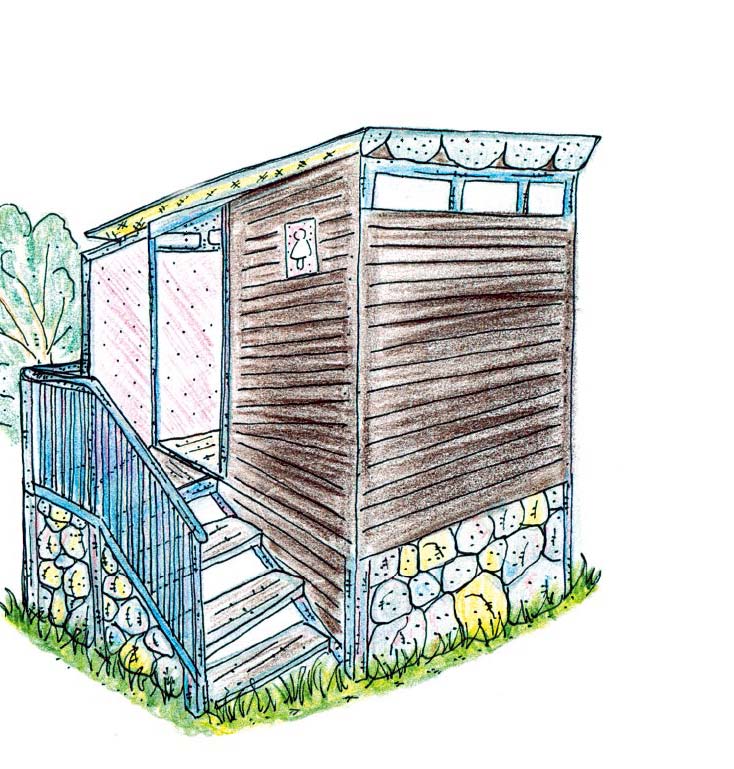

The book is an account of their interesting semi-wild life, highlighting activities like building a fire stove, constructing housing facilities, planting crops, cultivating chickens and sheep, and watching birds and other wildlife. They share skills they learned from daily life, ranging from identifying tools and burning firewood to building dry toilets and repairing log roads.

After living in urban areas almost their whole lives, the couple gradually embraced the unique features of the new environment and found ways to use natural materials through seemingly clumsy practice as they discovered the joy of working with their hands.

They carefully observe their wild “neighbors” and recorded their unique growth stories and habits, including both wild and domestic plants and animals—cute but ferocious leopard cats, mountain lizards that move like wind and freeze like pines, domestic geese, sheep, rabbits and dogs, various fungi, and Polygonum orientale in front of their door.

In the book, they shared their own paintings of herbs they planted as well as their home recipes including Chinese-style braised pork in brown sauce, Vietnamese-style rice noodles soup with beef and coriander, and a curry dish they learned from a Nepalese chef. Using different natural ingredients in different seasons, they outlined a tasty and self-reliant lifestyle from the fields to the dining table.

In their eyes, nature is not some distant wonderland, and cities are not concrete jungles, either. The Beijing suburb and northern hills that seem insignificant and indifferent are actually full of wild secrets and compelling stories.

There, hard work is required every day. They cultivate the land, cook meals, sleep on a brick bed, repair houses, feed animals, and even have to chase down “prison-breaking” sheep and drive away “invading” pigs.

“Rather than drop readied pleasures in our open hands,” they wrote, “satoyama fosters opportunities to create and polish pleasures with our own hands to sculpt them into lasting happiness.”