New Life for the Rhino-Shaped Zun

The ancient Chinese might have been greeted by rhinos in the Minshan Mountains in southwestern Gansu and northwestern Sichuan provinces, as evidenced by The Classic of Mountains and Seas, a geographical and cultural account of China in the pre-Qin period thousands of years ago. Nowadays, people in China can find the “animal” at the National Museum of China (NMC) in Beijing.

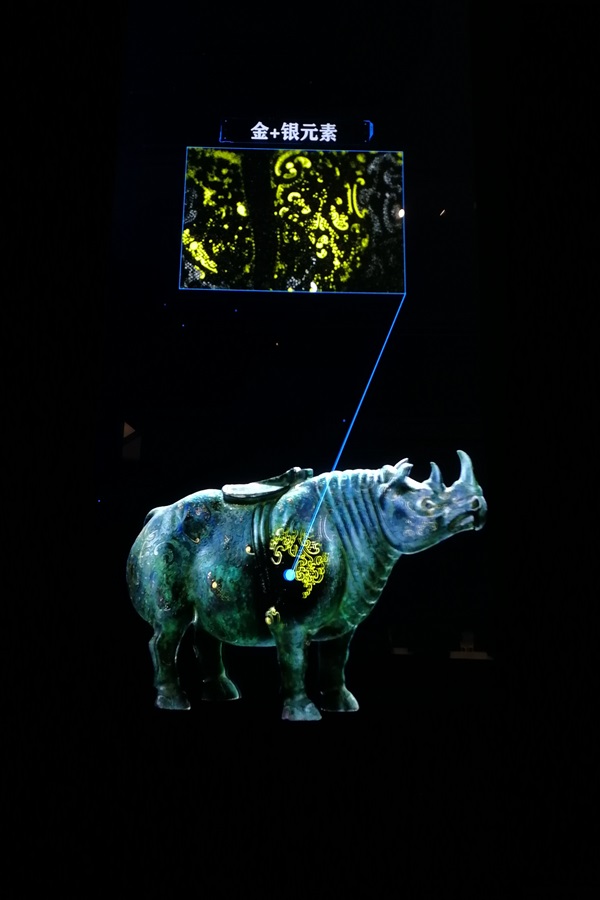

An exhibition called “The Digital World of Rhino-shaped Vessel” is now showing at NMC, featuring a smart display of its exhibit—a bronze rhino-shaped zun (wine vessel) inlaid with gold and silver cloud designs.

Across five sections, the exhibition uses digital technology to relive how this vessel was excavated, its functions in ancient rituals, the casting and ornamental techniques involved, and the historical context.

Delicate Craftsmanship

The ancient vessel was unearthed in Douma Village of Xingping County, Shaanxi Province, on January 11, 1963. Inside it were 17 objects including a bronze mirror, a belt hook, a file, and some scallop shells. Since most of the artifacts date from the Western Han Dynasty (202 B.C.-8 A.D.), some archaeologists inferred that the objects were buried in that period. The application of 3D printing technology helped reproduce the excavation site in the first section of the exhibition, “Craftwork Inspired by Nature.”

Contrasting other ancient civilizations where bronze casting skills were usually utilized for making production tools or weapons, in ancient China, they mainly worked for ritual purposes. According to The Book of Rites, a container used to hold liquor is called zun. The exhibited rhino-shaped zun is a distinctive liquor container with a lid on the back and a spout on the right side of the animal’s mouth.

In ancient China, bronze was also called jijin, which translates as “auspicious metal.” The second section, “Masterful Craftsmanship,” showcases the excellent bronze casting and ornamental techniques used to make this vessel, with the help of advanced testing technology and X-ray fluorescence imaging.

Professionals employed X-ray detectors to find spacers in many parts of the object and determined that the head, four legs, and abdominal wall could be pierced by X-rays of the same intensity. It can be inferred that there are cores inside the head and legs, which evidences the use of piece-mold casting. Interactive displays at the exhibition enable visitors to decode the material mechanisms, internal components, and casting techniques of the vessel.

Interactive displays at the exhibition decode the material mechanisms of the bronze rhino-shaped zun. (Photo by Liu Chang/China Pictorial)

The whole object is decorated with inlaid gold and silver cloud patterns as thin as a hairspring, an ornamentation method unique to China. This method emerged in the Spring and Autumn Period (770-476 B.C.) and was widely used to decorate bronze utensils, chariots, horse gears, and weapons in the period from the Warring States Period (475-221 B.C.) to the Western Han Dynasty.

Though inspired by nature, art often transcends it with a timeless representation of unique cultural motifs. The third section, “Beauty of the Zun Vessel,” further explores the elegance and vivid nature of the heavy bronze and the divinity under its rough skin.

A close-up of the vessel shows that the rhino represents stability, support, and strength, exemplified by its wide back and chest, stumpy but powerful legs, and round rump with a short, crooked tail. Chinese bronze ware decoration involves a series of multi-faceted visual symbols: animal patterns such as taotie (a ferocious and voracious mythical beast); simplified or abstract animal patterns such as curved and hook forms and waves or double rings; and nature-inspired patterns such as clouds. The cloud patterns applied on the vessel point to the idea of divinity. One highlight of the exhibition is the application of pinhole imaging, which empowers visitors to become “researchers” and examine the gold and silver ornaments on the vessel’s surface with a high-definition microscope.

Smart Inspiration

The vessel features an image of the Sumatran rhino, a creature that lived in ancient China. The fourth section, “Source of Inspiration,” features rhinos in ancient Chinese books and a map of geographical distribution of wild rhinos in Chinese history.

In ancient times, rhinos were quite common across China. Their bones have been found many times in the Neolithic sites and armor made from rhino skin was reportedly admired by warriors in the Spring and Autumn Period. But due to factors like climate change and large-scale hunting, the rhino as a species with low fertility was wiped out in the north. It disappeared in the Guanzhong area (now the central Shaanxi Plain) by the late Western Han Dynasty. The time-honored vessel stresses the importance of respecting and promoting harmony with nature.

In recent years, NMC has been advancing construction of a smart museum by harnessing cutting-edge information technologies, such as big data, cloud computing, blockchain, and artificial intelligence. The fifth section, “Interactive Smart Museum,” leads visitors down a path characterized by acute perception, ubiquitous interconnection, intelligent integration, autonomous learning, and iterative improvement by displaying high-definition details of the relic alongside scientific findings. A digital platform even details the comprehensive operation of the exhibition including real-time location, thermal information, visitors’ trajectory, popular exhibits, and environmental indicators.

High-definition details of the bronze rhino-shaped zun. (Photo by Liu Chang/China Pictorial)

“Visitors can enjoy an interactive experience at the exhibition,” said Zhu Xiaoyun, curator of the exhibition. “But we’re not just showing off technology or revitalizing cultural relics just for technology’s sake.”

“When technology revitalizes cultural relics to the point that they really tug at people’s heartstrings, they truly come alive,” she added.