Reflection in the Mirror. Xu Bing: Thought and Method

From July 21 to October 18, 2018, the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art (UCCA) presents an exhibition titled “Xu Bing: Thought and Method.” This exhibition marks the most comprehensive retrospective solo show of Xu Bing, a Beijing-based renowned Chinese contemporary artist. It is the culmination of his artistic career spanning more than four decades, featuring more than 60 works including prints, drawings, installations and films as well as documentary footage and archival material.

One of the most influential Chinese artists on the international stage, Xu Bing has made a profound impact on the history of Chinese contemporary art with his avant-garde works and wide-ranging practice. UCCA Director and CEO Philip Tinari believes Xu is not only the most representative icon of Chinese contemporary art but also a key figure for global contemporary artistic interlocution over the past half a century.

According to Tinari, the title “Thought and Method” expresses UCCA’s desire to provide a systemic overview of Xu’s notions and methodology in art creation, as well as the motivation behind his unceasing inquiry.

Xu’s works at the exhibition have been divided into three sections. The first section features Xu’s works dating back to the period from the 1970s to early 1990s, when he studied and worked in China. The second section highlights his works from the 1990s to 2008 when Xu was living in the United States. The third section focuses on Xu’s works after he returned to China in 2008. “For me, the exhibition provides a chance for retrospection,” Xu said. “Showing all the works together makes a mirror reflecting myself.”

Early Production Based on Writing Systems

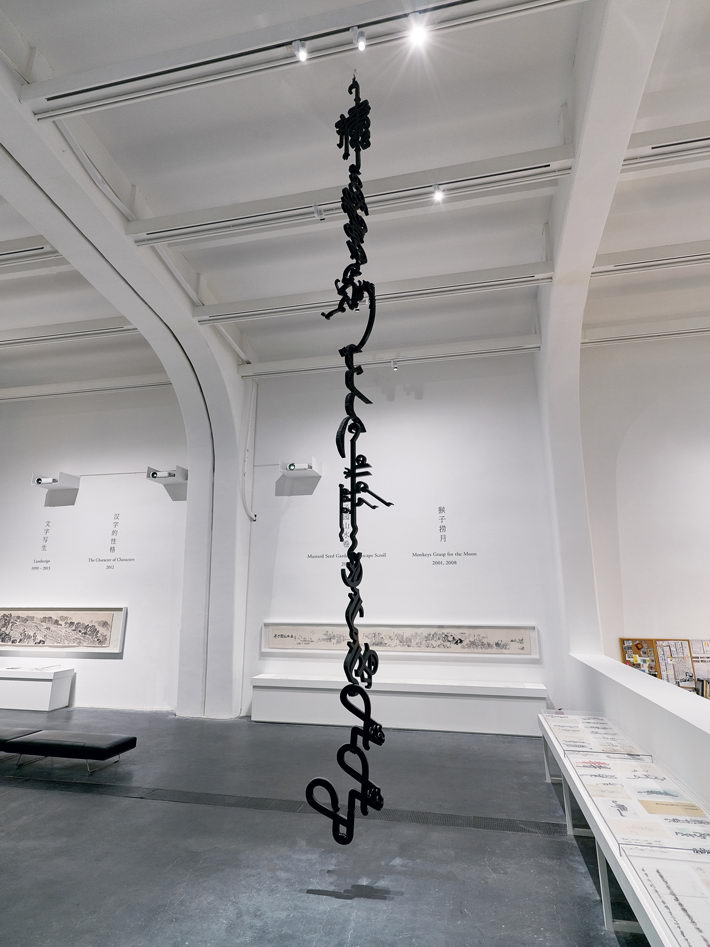

The exhibition starts with Xu’s early masterpiece Book from the Sky (1987-1991) which took four years to complete. The piece is a four-volume treatise carved with thousands of meaningless Chinese characters, each designed by the artist in a kind of typeface font originating in the Song Dynasty (960-1279) and standardized by artisans of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). The volumes are manually bound like ancient Chinese books.

This work serves as the introduction to Xu’s “Thought and Method.” Text is normally used for reading and conveying literal meanings, but Xu’s Book from the Sky is marked by illegible character-esque writing. Xu Bing wanted these “fake Chinese characters” to challenge people’s inert thoughts and drive them to doubt their available knowledge system.

Book from the Sky debuted at the National Art Museum of China in October 1988 and quickly caused a sensation at home and abroad, consolidating Xu’s reputation and academic status in the international art circle. Returning the work to UCCA is especially meaningful because it was displayed at UCCA’s opening exhibition “’85 New Wave: The Birth of Chinese Contemporary Art” in 2007 in the exact same space.

Exploration in Cross-cultural Context

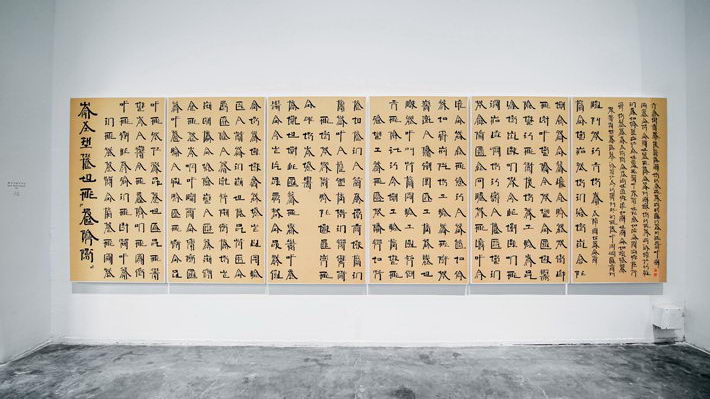

Exploration based on writing systems has remained a central theme of Xu’s production. Back in the early 1990s when Xu first moved to the United States, his greatest challenge was communication. During his experience of the cultural collision between the East and the West, he began creating Square Word Calligraphy (1994-present), a refashioning of the English alphabet according to the structural logic of hanzi (Chinese characters).

Contrasting his “fake Chinese characters,” Xu’s Square Word Calligraphy can be read, combining Chinese calligraphic art with English writing to create a new “species” that poses questions for people from both cultures. In 1999, Xu Bing was awarded a MacArthur Fellowship, popularly called the “Genius Grant,” for his work. In 2015, Xu collaborated with Foundertype, a Chinese font developer, to release “Foundertype Xu Bing,” a conceptual art-deco font that reorganizes the pinyin system (romanization of Chinese) into characters themselves. This work brought Xu Bing’s aesthetic ideas into the lives of the general public.

For the exhibition, Xu Bing created an installation piece modeled as an “adult literacy class” to serve the exhibition space with textbooks, an instructional video and calligraphy tracing books used in classrooms. As visitors enter the gallery, they also enter a “classroom.” Writing and watching videos create a more immersive experience.

Xu also embarked on a series of “cooperative endeavors” with non-human actors such as animals. Works like American Silkworm Series (1994-present), Panda Zoo (1998) and Wild Zebra (2002) all fuse Western form with traditional Chinese elements to address the frustration and excitement of transcultural contact.

Attention to Social Issues

In 2008, Xu returned to China and became vice president of the Central Academy of Fine Arts. The country’s rapid development inspired him to create a number of works including Background Story (2004-present) and Phoenix (2008-2013). Against a wider social and cultural background, these works review social phenomena and

the cultural identity of contemporary China.

A large-scale installation, Phoenix measures 28 meters in length and six tons in weight, making it too large to be placed in the exhibiting hall. So the exhibition only displays manuscripts and video materials of the work. Made of construction waste and abandoned tools, the work looks to a future built of recycled materials and their accompanying spirit, a familiar trope in both China and the world at large.

Xu’s close scrutiny of society has helped him produce a new work every a few years as he works to break traditional boundaries of art.

“An artist is actually devoted to building a closed circle in terms of his or her own artistic methods,” remarked Xu after reviewing his works over the past four decades. As for his future plans, he had no answer. “My works are not planned out,” he explained. “All I can say is as long as I have energy, I will continue to focus on social issues or Chinese themes. If I have something new to say, I will find a new way to speak.”