Wisdom and Light of Traditional Chinese Medicine

The history of the Chinese nation features an epic struggle against diseases. Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) has emerged and developed over thousands of years to gradually form a distinct and unique outlook on life, health, and disease prevention and control characterized by the profound philosophical thinking of the Chinese people.

To celebrate TCM culture, the “Light of Wisdom: Traditional Chinese Medicine Culture Exhibition” recently kicked off at the National Museum of China.

The exhibition features more than 500 cultural relics covering jade wares, ceramics, bone and metal objects, ancient books, calligraphic works, paintings, revolutionary relics, and more, supplemented by more than 200 medicinal materials.

Divided into five sections, the exhibition adopts various perspectives of TCM such as its history, prevention and treatment concepts, medical classics, medicinal herbs, diagnosis and treatment instruments. In addition, the exhibition provided insights into prospects and international cooperation in this field through numerous digital images and interactive items that covered the long history and unique concepts of the TCM cultural system.

The first section, “The Key to Civilization,” analyzes TCM as a key to open the treasure trove of Chinese civilization. In the exhibition hall, many classic books and exhibits tell various stories about TCM development and interpret ideas of “treatment based on syndrome differentiation,” “harmony between man and nature,” and “balance of yin and yang,” advocated by TCM culture.

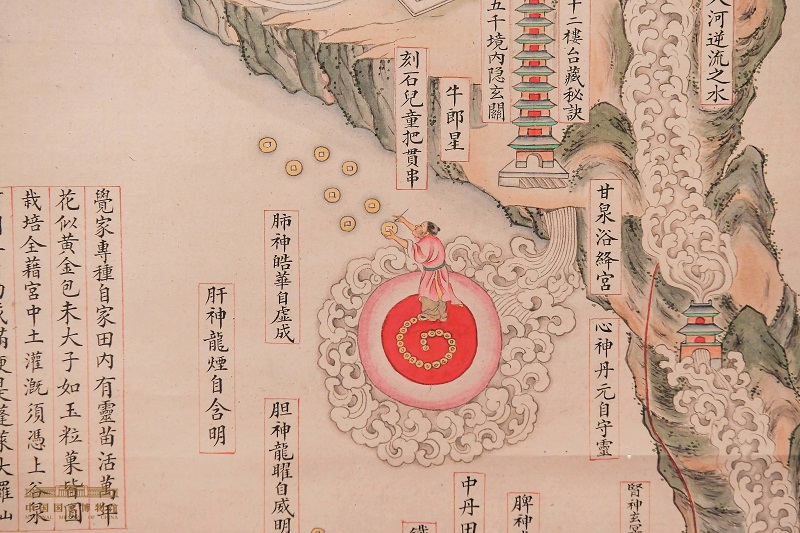

The realistic traditional Chinese painting Neijing Tu (Chart of the Inner Warp) from the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), illustrating Taoist “inner landscape” of the human body, aligns with the ideas of TCM. The outline of the diagram roughly depicts a sitting person practicing meditation. Inside the body, a small world with various landscapes such as hills, rivers, fields and cattle was portrayed, reflecting the idea of “harmony between man and nature.”

The section “The Way of Health Preservation” shows how ancient Chinese attached great importance to health and used various strategies to maintain physical and mental health. The ink-and-wash painting Lu Yu Brewing Tea by Zhao Yuan from the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) vividly presents a scene of Lu Yu, the Saint of Tea, brewing tea leisurely in mountains and waters. In his Classic of Tea, Lu Yu likened tea to ginseng in terms of nutrition and proposed drinking tea to promote self-cultivation based on its function for health preservation.

Many gathered in front of a silk scroll excavated from the Mawangdui tombs of the Han Dynasty (202 B.C.-220 A.D.) in Changsha, central China’s Hunan Province, which is the earliest known illustrated physical fitness instructions based on the movements of animals including birds, bears, and monkeys. Some visitors couldn’t resist imitating the movements depicted on the silk scroll. Based on the illustration, Hua Tuo, a famous physician and surgeon in the Eastern Han Dynasty (25-220 A.D.), created the Five-Animal Exercises according to the gestures of tigers, deer, bears, monkeys, and birds.

The third section, “The Secret Classics of Linglan,” combs the history of categorization of TCM. Divisions in this field began in the Zhou Dynasty (1046-256 B.C.) according to the book The Rites of Zhou and took shape in the Tang Dynasty (618-907) in terms of different targeted body parts and methods. From the Yuan Dynasty to Emperor Longqing’s reign of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), the royal hospital gradually opened 13 departments including pediatrics, internal medicine, and orthopedics. The fragmentation marked an important leap in the development of TCM. This section of the exhibition features many ancient classics related to TCM including many precious rare books and manuscripts.

The most striking item in this exhibition area is a bronze acupuncture figure made in the Ming Dynasty, part of the museum’s collection. It is a replica of bronze figures produced during the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1127) that were life-sized with hollow chests and abdomens. The surface was cast with jing and luo, regarded as a network of passages through which energy circulates and the acupuncture points are distributed. Such a bronze figure was used to train medical students’ proficiency in acupuncture technology in ancient times. To use it, a layer of wax was applied on the surface and water was injected into the body. If it was pricked accurately, the water would leak out.

Diagnostic and therapeutic instruments as well as pharmaceutical tools are indispensable parts of the TCM system. The fourth part of the exhibition, “The Instruments and Medicines of TCM,” displays a variety of herbal medicine cutters, mortars, and stoves, as well as ancient pharmaceutical methods that once relied on manual processing. It also demonstrates methods of practicing medicine in the streets.

Originating on the land of China, TCM has gradually spread around the world while continuously absorbing the achievements of other civilizations to be enriched. The last part, “Inheritance and Innovation,” shows how TCM was already spreading to neighboring countries and exerted a significant impact during the Qin (221-207 B.C.) and Han dynasties. China’s smallpox vaccination techniques, for example, spread throughout the world in the Ming and Qing dynasties. An ancient book titled New Book of Vaccination describes how Chinese people fought smallpox in the past. The Compendium of Materia Medica, which is considered the most important and influential text in the TCM community, has been translated into many languages and distributed worldwide. Charles Darwin called it “the encyclopedia of ancient China.”

In the center of the exhibition hall is the “medal counter” of Tu Youyou, a famous Chinese pharmacist and laureate of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. Her discovery of artemisinin greatly reduced the incidence and mortality rates of malaria around the world. “Chinese medicine and pharmacology are a great treasure-house,” she said in her acceptance speech at the Karolinska Institute in Sweden on December 7, 2015. “We should explore them and elevate them to a higher level. Artemisinin was explored using this resource. From our research experience in discovering artemisinin, we learned the strengths of both Chinese and Western medicine. There is great potential for future advances if these strengths can be fully integrated.”